|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 23 | Chapter 22 | Chapter 1

Daisy returned to school at the end of the holiday, thoroughly in love with her friend. She carried with her his

assurance of undying affection, also a promise to solve all her difficulties by correspondence. His advice was that she make unusual effort to gain

admittance to the Philomatheans by earnest endeavor to cultivate a habit of correct speaking: Slang was expressive, he granted, but like all strong

things was to be used sparingly and only under stress of feeling, which should occur very seldom in a young lady's life. Daisy, duly impressed by his

large terms, especially when he threw in several references to the psychology of the matter, predicted he would be proud of her when they met once more

during the spring vacation.

He sincerely missed the companionship of the Tomboy, her childish confidences, her freshness of view. Her insouciance

acted as a stopgap in the stream of doubt which made up his thinking life; he prided himself that in her he had the eternal feminine in miniature, that

somehow in studying the child, he was learning whether the concrete joys of life were worth more than the abstract. Though in a jocose mood when promising to write faithfully, he found great pleasure

in living up to his guarantee, often allowing more serious matters to give place. Daisy, immediately on her return to school, announced her probation

for admission to the literary society, and her abstinence from street English was a source of gratification to her teachers expressed in the monthly

report to her father. Her weekly effusion at the beginning of the second semester contained the joyful news, her efforts had been crowned, she was now a

member in good standing "thanks to her Mentor and ever-loved advisor." Slang had given way to stiltedness, but he was convinced the change would be

beneficial to Miss Daisy.

Reading one of the child's letters he walked into the editorial room, saluted his chief, refusing to listen to

discussion of current events until he had indited an answer. In the middle of the sixth page he asked Galt for the elucidation of a problem in

higher arithmetic, and when the editor failed to satisfy him, called in Higbee, disturbing the morale of the plant until Daisy's demand could be met by

the united intelligence of the staff. After sealing the letter, he said:

"At your service."

"That was a very important communication," nodding towards the letter.

"It is in answer to a request for information from a child, old man, and to give it I would interfere with the running

of a far more important machine than the Emmitsburg Chronicle; to tell the truth, children are the only ones worth while anyhow."

"0, I don't know," rejoined the editor, "there are others; even 'Bonus Hoinerus aliquando dormitat.'"

"Hurrah for Old Horace! You love him, too?"

"Is that his? I thought it was Mr. Dooley."

"Who runs the educational mill in this burg, are you subject to a board elected by the omniscient popular voice?"

"We have a committee which accept teachers because they have their 'stiff ticket.' "

"Of which the Annans are a great part?"

"The same, though they work through their able lieutenant, Eichelberg."

"When do you hold your next election for members? "

"In April; we shall take a hand?"

"And begin a campaign of instruction for the holders of the glorious franchise immediately," taking pad and starting

his article.

It was an easy task for the Professor to deliver a broadside against the system of control of education by a board

chosen by the votes of the few interested parties, who looked for financial patronage. The attack was illustrated by reports of experiences where

publishing firms had given substantial bonuses to people who could influence the introduction of textbooks into a school system. It was a ease of

holding up his chosen vocation to censure, and the editor deemed it wise to point this out when the copy was referred to him for approval.

"But since I know whereof I speak, since the teaching profession is a victim of the graft-spirit in some quarters, why

not make it public that a remedy may be found? Humanum est errare, no institution is too sacred to be free from frailty and public criticism is

the most potent remedy. For that matter I doubt if my chosen field shall ever see me in harness again."

"Are you going to stay with us?" quickly. "Who knows?" evasively.

"You might touch on the holiday nuisance in that copy, take a fling at flitting day, apple-butter day, hog-killing day,

the children lose too much time from school."

"What have you been doing, reading G. Bernard Shaw?"

"Why do you ask?"

"You seem to be impregnated with the utilitarianism of the witty though unhumorous Irishman; you shall be advocating

vegetarianism next. Let the people have holidays, it keeps their roots in the soil, it saves the children from a portion of the leveling influence of

mental development."

"You have a new philosophy, haven't you?"

"Not original, though; it's Richter's, 'Love God and little children.' "

"You might put the latter member into more real execution," with a laugh.

"Go to the devil," sending out his copy.

The article was received with loud protests by the parties most interested; Annan who had been advertising the public

that three per cent could be had on all time-deposits in the Emmitsburg bank, peremptorily ordered his advertisement should cease. Father Flynn, more or

less reticent in strictures lately, wrote a long letter to the editor bewailing the misguided zeal which led a man to throw mud at his own profession,

and defying the author to produce instances of the venality mentioned, a very safe procedure on the Doctor's part. Eichelberg looked up the libel law,

deigning to consult his disdainful antagonist, Seabold, in effort to obtain knowledge. Syl Stoner, having learned from careful perusal of the article

that the educational problem was personal to him in view of his houseful of rising citizens, discussed the matter with Carrigan at the carriage shop.

Education was added to the list of subjects for debate in the store assembly, and a strange unanimity that reform was needed prevailed. Isaac Annan,

with finger on the common pulse, realized something should be done to check the growth of independence amongst his victims. Feeling that the threat of

tar and feathers was not likely to be carried out now that Maggie Sharpe had returned from the hospital, bearing evidences of a serious spinal

operation, he grew bold enough to talk of suing the Professor for sundry verbal assaults. Not cognisant of Dr. Brawner's change of heart, he broached

the subject to the physician:

"I wouldn't do it, Ike," advised the Doctor, "that boy's pretty smart, a bad one, I take it to fool with."

"With the College on our side, and Gerry on the bench, I think we could make him sweat."

"The College has had enough notoriety in its clashes with him, you can't count on them. As for Gerry, in a go between

you and Seabold, for it would come to that, you better think twice. Don't forget what the Judge owes Seabold since last November."

In the exchange of gossip, the hardest working and steadiest running process in the village, this conversation reached

the ears of the dentist, who dearly loved an altercation in which he had no part. More-over his admiration for the Professor had not been weakened by

the current rumor that Harry had helped keep him out of the factory company. He felt he should tell the latest.

"You know that overcoat you promised Ike Annan, Prof?"

"Was I so generous?"

"I heard so."

"What of it?" quietly.

"He's thinking of suing you for threat."

"Dr. Forman, I never thought I could be brought to hate anyone in this world, that any person could interest me

sufficiently to awaken the passion. But that fellow is such a hypocrite I fear he has brought me dangerously near to it. Now tell him for me I promised

him that decoration on one condition namely, that his story reach the ears of the young lady or her family, and that condition still exists. If I find

out they have suffered for a moment, he shall get his overcoat as sure as God made me. I am not done with him yet by any means."

Emmitsburg had a charter granted when the United States was young, so young indeed that the borrowing capacity of the

village was limited to one hundred and fifty dollars. Absolutely nothing in the nature of public improvements, except the keeping of the grass down on

Main street, could be undertaken. The consequence was private capital, meaning the Annan and their coterie, put in the

water system and controlled the rates for town and private consumption. These

enterprising citizens dammed a watershed in the mountains, piped the town, and sat back drawing increments on the original outlay. Gravity took the

place of machinery, nature worked in the interest of the Annan family and to them that had was given. All other public concerns were geese laying golden

eggs for those whose greediness eventually brought about their death.

Seabold, seeing from his entrance into the life of the town, that such a condition of affairs needed remedy, worked

single-handed to bring it about until Galt and the Professor joined forces with him. His first triumph was registered when the Federal Government took

the post office out of the ring's hands, then success followed success until now he was ready for the grand coup which meant a new charter for

Emmitsburg. His methods were those sanctioned by recent politics, not open to too close scrutiny, but the ones he found to hand, as he told his friend.

Gerry in his late campaign, needed the help of those of democratic affiliation, Seabold got it for him, and in political gratitude the court was ready to

make fitting return. In due time (1906) the new charter was granted, the borrowing capacity raised to an amount equaling the assessed valuation of property,

and the town fathers besides voting a new lighting system to replace the oil lamps, made provision for a

village water-works. The Chronicle assisted by a crusade against the wells, which supplied the houses of the people who could not install town water

because of the hitherto exorbitant rates.

Annan was at his wits' end, at first vowing he would spend his every cent to cling to his rightful inheritance, but

learning that springs were to be purchased, he lost heart in the struggle, offering to sell at his own figure. The Professor, the editor, Seabold and

Peter Burket, drew up an appraisal of the property, allowing at the grocer's suggestion, fifteen per cent for the investment, and this was submitted in

turn to the council, who through Uncle Bennett referred it to the present owners with the assurance they might take it or leave it, but that it stood.

The town eventually assumed control of the water plant, all houses were piped, the wells closed and typhoid became a memory.

Peter Burket was growing tired of the grocery business, of its eternal bickering with bargain hunters and people

endeavoring to get something for nothing. He had been successful through honest dealing in laying up a few thousand dollars, and now was inclined to

take the world easy, to fish Tom's Creek and Flat Run in season and occasionally to journey to the Monocacy, where sporty bass were found. No issue had

blessed his marriage, thus freeing him from the incentive of amassing a fortune. Still in the prime of life it seemed a shame the town should lose the

services of so sterling a citizen in the time of its active development.

In conversation on the subject, Peter expressed a willingness to participate in any movement which would furnish him a

field for work without demanding too much of his time. Harry thought long on the matter, while the merchant looked about for someone who would take his

present business, but finding none to buy, sold out at auction. It was a blow to his sense of fitness to sell without being sure of his fifteen per cent

but the call of leisure coupled with the approach of the open season for trout was strong enough to win him over.

At a meeting of the factory board, of which Peter was a member though not present, the Professor brought up the

grocer's retirement, stating his reasons for so doing, for he considered it a matter of importance to all well-wishers of Emmitsburg. The editor was of

opinion Peter might be interested in the actual management of the factory in the capacity of outside representative, his duties being to look to the

obtaining of orders. The proposition seemed good to the assembled directors except the lawyer, who in no uncertain terms declared he had other duties in

view for Peter. These he was in no hurry to disclose and the meeting adjourned without further action, though with some private criticism of Seabold's

secretiveness. The editor, in after conversation, adverted to the matter:

"Seabold might have let us in on his project," he said, "he surely cannot doubt our discretion."

"He has been fighting so long in silence," apologized the assistant, "it has become a habit with him. Jim reminds me of

a certain reformer I met in Europe. This man began the battle for popular uplift absolutely alone, his most powerful weapon being ability to keep his

own counsel. His mere silence worried his opponents more than any open fight would have done. Being driven to dinner with his most ardent supporters on one occasion, they passed a regiment which was holding a sham battle. As the defense

was forced back the attack moved forward to its newly-acquired position, making ready for further advance. At table the leader was asked what his next

move would be, after obtaining his present half measures. Every man present was a tried and trusted friend, there was no apparent need of secrecy, yet

after an eloquent period of silence he asked simply," When the attacking party had gained an advantage this afternoon what did they do?" The poor devil

never finished his work, a woman killed him politically first and really afterwards, but his testament of silence in the characters of his successors is

bringing his work to a happy issue. We must bear with Seabold's methods."

The work the silent one had in view for Peter, and which he made known to the others in his own good time, was none

other than the opening of a national bank for Emmitsburg, which would take financial control out of the hands of the Annan. In preparation the ex-grocer

disappeared from the village temporarily, going to the city to learn phases of his new calling. His ability to assimilate knowledge added to his well

developed business instincts and minute care for the smallest detail stood him in good stead; the demands of the banking world in the territory not

being great, he was soon fully capable of coping with them as the exigency arose. One influence exercised by the Professor in fitting the new banker for

his work was teaching him more correct use of the vernacular, and any person consulting the present cashier of the Emmitsburg Savings Bank is not

likely to be told a matter, "can't be did."

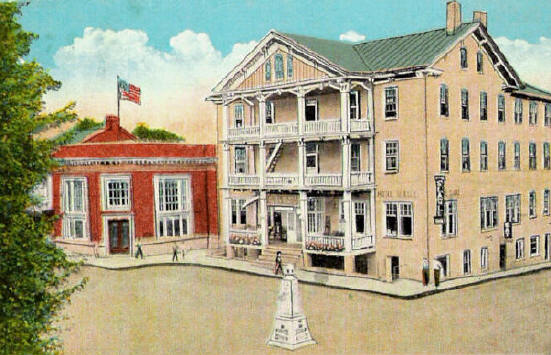

Red Building is Emmitsburg National Bank - Four story building is hotel Spangler

All these things filled the days of the Professor, distracting his mind from thoughts of his personal problem, but it

harrassed him in the lone watches of the night. He had recourse to books, not that he thought they contained enlightenment for his perplexity, but that

he might talk to the masters, feel their ancient charm, permit them a fair field in the struggle. Somehow he felt, if he ever followed his inclination

of heart, the days of philosophy would be over. For hours at a time the face of Marion faded under the spell of the abstract, only to revive when he

laid down his books. He saw as little of her as was consistent with their well-known intimacy, telling himself she, too, should have a square deal.

Months passed, and thought added not one inch to his mental stature. The solution of all life's problems is a leap in the dark.

Chapter 24

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|