|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 6 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 1

A ride over the adjacent battlefield, which necessitated the spending of a whole day in the saddle, rendered the

Professor disinclined to further strenuous physical exertion for some time, hence he was seated under the large horse-chestnut tree in the yard of the

rectory, pad in hand, sketching notes for the "Question and Answer" column of the Chronicle. Reviewing the scenes of carnage enacted by the flower of

American manhood had not tended to lighten his spirits. His survey of the three days combat, of the heroic assaults and repulses between men whose

brother love had turned to hate, caused the names of "The Wheatfield," "Bloody Angle," "Devil's Den," to run through his brain in harmony with the beat

of his horse's hoofs. The famous charge which men have whispered was the outcome of the order of an insane commander, what would it have been called had

it succeeded? The abandonment of their almost impregnable position by the Union forces, which it is said was seriously contemplated after the first day,

would have led to what results?

Riding home in the dusk, as he pulled up the jaded Admiral for breath at the top of a steep hill, he repeated to himself, for he was an egoist, his summary of the day's impressions couched in the words of the hero who

prayed while others fought, "With charity towards all, malice towards none; to do the right as God gives me to see the right."

Throughout the day deep in his subconsciousness, the effort to puzzle out an explanation of Marion's dissection of his

character accompanied, and now as he wrote vexed him. He was surprised to find such astuteness in a young woman of Emmitsburg.

"Oh! I say Professor, just a moment." It was the manner of Mr. Halm, in opening a conversation though the person

addressed were giving no signs of haste to reach a particular point. Harry lowered his feet which were planted against the tree, arising to greet his

visitor, at the same time brushing ashes from his waistcoat and cravat. Though the elderly man appeared to have but a moment to spare from some pressing

duty he thankfully accepted the proffered cigar, seating himself leisurely.

"What I was going to say, Professor—don't you think it's a beautiful morning?"

"Glorious," offering a match.

"What I was going to say—these are very good cigars, you don't buy them in Emmitsburg."

"No, I have not, so far, patronized the home market in its tobacco phase."

"Don't, my dear Professor, the grade they make here is abominable; old Whitmore sells them for a dollar a hundred."

"Whitmore? Oh, yes, he is Uncle Bennett's theological antagonist."

"That's he; at one time the Deacon was a preacher and exhorter through the county but resigned to manufacture cigars

for local consumption."

"Yet critics say the Gospel comes high," laughed Harry.

"But what I was going to say—have you read this week's Chronicle?"

"Even to the advertisements, some of which I have been reading in country papers since my primary school days."

"I think Mr. Galt a wonderful man," ignoring the sarcasm. "Take that article on 'Love and Humor, Wit and Hatred,' that

I think could grace the pages of any New York paper."

"Yes?" endeavoring to hide his elation.

"Yes, indeed," went on the old man enthusiastically, "and what I liked particularly was the strong appeal for mutual

help, charity for the shortcomings of one's neighbors, and especially that phrase: 'We laugh with those we love, we laugh at those we hate and despise.'"

"I presume the writer felt deeply on that point." "Do you think the editor had any local reference?" "I really couldn't

say."

"What I was going to say—don't you think you could take tea with us some evening?"

"Thank you, Mr. Halm, it will give me great pleasure, I assure you."

"The pleasure shall be all mine, but what I was going to say—don't you think there could be a better social spirit

amongst the people here?"

"I am not very well acquainted with the social atmosphere, being as you know, almost a total stranger."

"You know they have very little money, that is most of them."

"I have not remarked a Metropolitan chase after the filthy lucre, nor a Pittsburgh lavishness in spending it, yet I

don't see that the lack of money should constitute a barrier to social harmony," said Harry dryly, amused at the other's tendency to stray from the

point.

"What I was going to say, Professor—that is don't you think something like theatricals, amateur theatricals, what I was

going to say, theatricals in which we could interest the young folks, would help to promote social concord?"

"Beyond doubt, could we arouse interest." "What I was going to say—what do you think of Miss Tyson's voice?"

"Disclaiming all critical ability, for my musical education is represented algebraically by zero under the radical, I

would say that Miss Tyson has the most beautiful voice I have ever heard."

"Wonderful! charming! superb!" enthused the musician, and then launched into a disquisition on pitch, timbre, tone,

color, and a hundred other things about which the Professor was in infantile innocence. Breath failing him at last, the other to fill the gap said:

"Miss Tyson's rendition of the lullaby was the sweetest thing I ever listened to."

"But you should hear her at the classics—what I was going to say—don't you think we might get up an entertainment?"

"I haven't the slightest doubt of it, but if you will pardon me I don't see exactly where I come in, that is what part

I am to have in it."

"You must do it all, that is, what I was going to say—you must organize it."

"Really you flatter me by overrating my abilities. I have never made an attempt in that direction, at least since I

left college."

"It is easy enough, that is, it will be easy for a young man of your attractiveness, the boys and girls shall flock

around you as a center of cohesion, so to speak."

The flattery was not lost on the younger man, the idea making appeal to him. He had already reached the conclusion that

in his search for moral equilibrium it might be better to get away from himself as much as possible. The long nights wherein he wrestled with his

malady convinced him of the hopelessness of contending with the demon in a hand to hand, silent contest. The Rector was sympathetic, but Harry had never

made his weakness a direct subject of discussion between them. After a few moments thought during which Halm watched him closely he said:

"I am willing to do whatever I can to make life pleasant for the people of this village, the one thing I fear, however,

is the animus of some towards me. Were I to be prominent in the movement it might cause friction."

"Friction, nonsense! What need you care? The parties who dominate this town may raise objections covertly, but they

dare not openly oppose what is elevating for the village folk."

"By the way, don't they do anything for the social uplift here?"

"Yes, that is, they allow certain selected ones to attend the commencement exercises, and during the holidays they have

a distribution of clothing at the Academy for the poor of the town. The most heart-rending sight I ever beheld, my dear Professor, worse any day than

New York's bread line. The tramps of the city are fighting for a dole, here it is a people accepting as a charity what rightfully belongs to them," and

the old man's indignation rendered him for the moment coherent of speech. Observing the pain and not wishing to prolong it, Harry turned the

conversation back to a former channel by asking:

"What would you suggest as our first line of endeavor in theatricals?"

"What I was going to say—would it not be well to begin with a minstrel show?"

"Perhaps, but as I understand the situation we shall have difficulty in getting a sufficient number of young men

together."

"What I was going to say - I have written a little opera, that is an operetta - nothing serious, a ' few tunes and

jingles strung together - but there are several numbers just suited to Miss Tyson's voice. Of course, we could not offer it as our first t venture."

"The very thing, let the people know they have a rival of Mascagni and Herbert in their midst, that shall be an

assertion which will tend to social uplift surely."

"Oh, no, no," entering a modest disclaimer, "I only wrote it with reference to Marion's voice." `'I shall speak to the

Rector, I am sure he will approve, in the meantime let us consider our forces, have we a soprano?"

"Miss Lansinger, the organist, is very good, if she will take part, " somewhat doubtfully.

"Why would she not?"

"She will I'm sure and we can have Doctor Foreman for basso, and young Marion is a very dear tenor, we shall get along

famously," the musician was pleased at the prospect.

"Then all that remains is to draw up incorporation papers; in a few days we launch 'The Emmitsburg Opera Company,' then

let the Metropolitan impressarios look to their laurels. Have another cigar."

"Oh dear! no, thank you, my wife sent me for something for dinner, I forgot, I must hurry along."

The Professor sat for some time in deep thought wondering if there were a place on earth in which contentment reigned.

His mind wandered back to his own college world, wherein the outsider thought he beheld the supremest peace and goodwill. He recalled the petty

jealousies, struggles for place, desire for the plaudits of students and all the other miseries that college flesh is heir to. The review was not

calculated to hearten him. Men, he pondered, who are set aside to think world-thoughts, who are supposed to seek truth at any cost, and yet whose every

action is overlooked by the "green-eyed monster." He was inclined to blame himself that, as most of his classmates, he had not gone into the big

business world where the fighting is on a scale worthy of a man's man.

As he thought of his present position he shuddered. The recollection of the story that would, long ere this, be afloat

at his college brought tears to his eyes. He was down and out; every student would know the facts embellished by the fancies of his fellow-professors.

"There is a certain subtle pleasure for us in the misfortunes of our dearest friends," he quoted to himself from the old French cynic, before realizing

that he was becoming morbid. Shrugging his shoulders, he picked up his pad from the ground and started for the Chronicle office.

On Main Street he came upon Miss Tyson and Halm talking. A thrill of pleasure at the young lady's improvement was

followed by speculation as to when Mrs. Halm would get her things for dinner.

Coming up to them he congratulated Marion, while the musician, again announcing his need for haste, made off. Offering

his arm to the girl who told him she was testing the strength of her ankle, they sauntered up the street.

"Isn't Mr. Halm an old darling?"

"Rather, he is several old darlings rolled into one."

"He was telling me of the operetta you are going to produce and humming some of the parts he has written expressly for

me. I am afraid, however, you are making a mistake in giving me a prominent part, my popularity is somewhat dimmed in Emmitsburg."

"What other young ladies shall be willing to take part?" ignoring her self criticism.

"I think they shall all be willing, as the rehearsals will give them something to do in the evenings."

"Will they be satisfied with places in the chorus? As I gather from the composer there will be but four or five leads,

that is solo parts, and two of those for men."

"There should be no difficulty in that, for me I shall be more than pleased with a minor position."

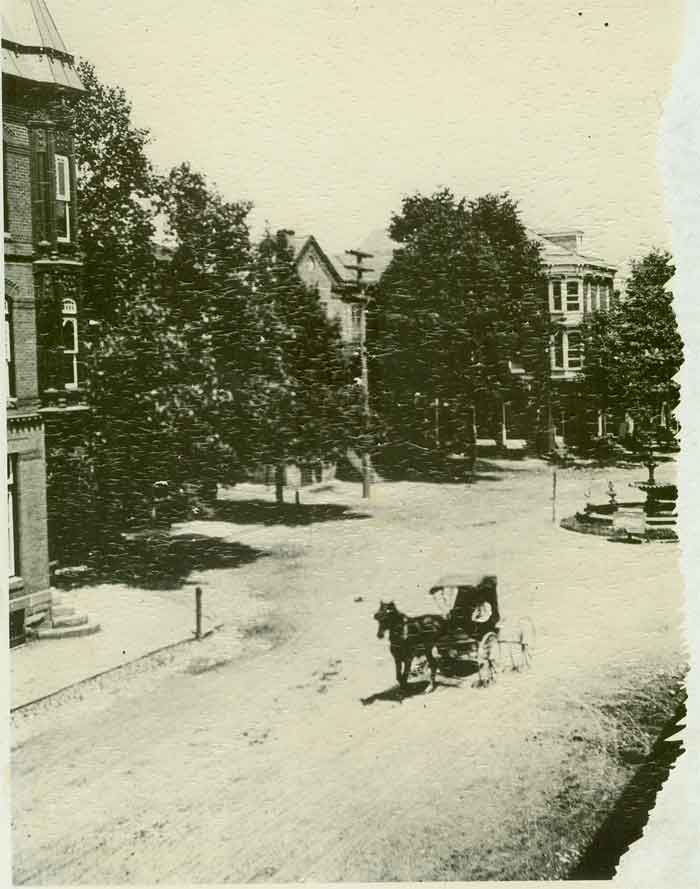

Emitt House ~ 1900

They had come to the Emitt House where the roads fork and the Professor looked inquiringly. The girl assured him she

was fully equal to a longer stroll, so they passed out the road on which they met a week before. The mountain chain stretching along to right and left

and towering into the clouds filled their vision. The fields of ripening corn unstirred by any breeze suggested the fruition of a life well-spent. Over

all was infinite calm, with a buzzard soaring lazily in the blue, as a discord emphasizing the harmony. Both young beholders felt the spell and searched

their minds for something appropriate to say. At last Harry uttered the common-place:

"How calm and peaceful this is. I love it."

"Love it!" echoed the girl with scorn, "I hate it. I enjoy spring with its riot of new life, I find pleasure in the

July sun though it scorch me, but autumn with its peace and calm, ugh! I hate it."

"You are young yet," said he sententiously. "You are not a patriarch yourself."

"No, but I have seen enough of the strenuous to enjoy a period of calm."

"I always thought the life of a college professor was one of humdrum and routine."

"The traditional idea," a little bitterly, "a bespectacled, long-coated pedagogue, strong on Greek and higher

mathematics, short on worldliness and horse sense; moving through life with the soft pedal on his voice and no red blood in his veins, drawing a

stonemason's salary and apeing the living of a millionaire. One who would be a joke in a man's world, hence is wise enough to be a pussy in a world of

women."

"Not so bad as that," apologized Marion glad to have stirred him so deeply, "but one who went the even tenor of his

ways, living in an atmosphere of abstractions, not condescending to the common-places of everyday existence."

"You do not like the calm of autumn," he said anxious to turn from a painful topic.

"I hate calm of any kind, it has been preached at me ever since I was able to understand. I was fired from the

St Joseph's Academy

because I could not appreciate the value of calm and pose and 'womanly dignity. I finished at a school in Washington amidst the predictions of the

faculty that there was a stormy future ahead of me. I am leading a terribly perilous existence now, don't you think?"

St Joseph's Academy

"You had the honor of being fired? I don't know how it is looked upon in female schools, but to be fired from college

is the open sesame to distinction amongst men. One of the leading lights of the country today was dismissed from the college over there."

Reaching a grassy spot beside the road, he invited her to sit and rest. There in the lazy September sun they talked of

boy and girlhood days without the least restraint. He told of his record in school, how most of his chums had quit before graduation and gone into

business. To everyone's surprise he had finished, adopted the teaching profession, had gone to a German university, learned to drink beer, returned and

accepted a chair. She told of her constant warring with the authorities at St Joseph's, how she could never see any wrong in being her natural self, and

how many punishments she had to undergo because she could not make convention of equal importance with the Ten Commandments. She never received a medal

nor honor as her deportment was a constant minus. At last with much show of feeling she asked:

"Do you know why I was dismissed?"

"For something very heinous, I am sure," laughing.

"We were up the mountain one day on a picnic, and after lunch we wandered along the bank of the creek to where it was

quite deep. Someone dared me to wade in. Of course I did it, and that was the very head and front of my offending."

"Very scandalous, indeed," he commented with mock gravity, not appreciating the depth of the girl's feeling.

"And it shall be told to their children's children unto the fourth generation. Do you wonder that I am weary of calm,

of pose, of dignity? It may seem a laughing matter to you to flout the conventions of a village like this but a girl must live. There is only one person

in this town who is sincere with me, that's Vinny (Vincentia) Seabold."

"A very charming friend, but cannot I be a second sincere person?"

"Prove yourself," simply, and rising to return. The walk back was rather a silent affair, observed by the knowing ones

of Emmitsburg, who wagged their heads and tongues. Passing the Chronicle office the editor waved out the window and wondered if his assistant had found

more attractive occupation than journalism.

Chapter 7

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|