|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 16 | Chapter 15 | Chapter 1

It was pay-day at College and Academy, a monthly event of importance, for real money was in sight. An hour off was

granted at the institutions that the checks might be converted into currency before the bank closed for the day. The employees were hurrying in, young

Mr. Annan passing out the coin of the realm, wearing a supercilious countenance such as eminently fitted him in dealing with people whose financial

rating was twelve dollars per month. Each check was diligently "shaved" before the money was handed over. Some of the recipients went straight to

Annan’s store to settle their grocery accounts; a few of the more independent crossing the Square to Peter's for the same purpose. One or two found

their account books in the paying-teller's hands, and received what was left after deduction; they were not to be trusted to transfer the money a few

steps.

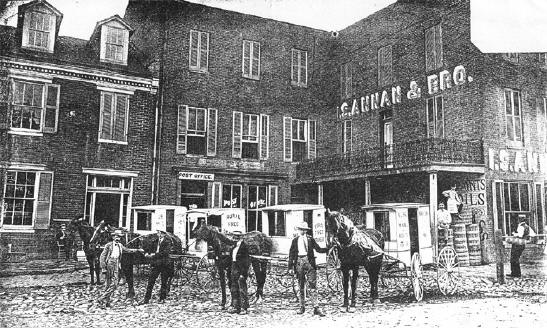

Annan & Brother's Building is present day Ott House Restaurant

Entering with the rush, the Professor stood one side as his business was not important. The cashier nodded graciously

on catching his eye, for his monetary standing had long since glossed over the rancor generated by his threat, anent Mr. Annan’s carcass. An old fellow

stepped out of line looking in a puzzled manner at the paper in his hand. In his trouble, he raised his eyes and saw the Professor, then a light seemed

to break for him. Coming over he asked:

"Konnen Sie Deutsch sprechen, Herr Professor?" "Ja, Meinherr, was wollen Sie?"

With a smile of satisfaction wreathing his face, for the moment, he asked him to read the amount of the check. On doing

so the troubled look returned and the old man continued in German:

"I can't understand it."

"What's the trouble?" wrestling with a patois of the language he had not used in months.

"It should be for twelve dollars."

"Perhaps you have lost time, are docked."

"Yes, that is it, I know now; but they might have let me have one half day in forty years. I worked for them forty

years and never lost a day. Last week I celebrated my seventieth birthday and my wife gave me a party; I remained from work in the afternoon, we had a

bottle of beer and I smoked a cigar. We wrote letters to my children, who have all moved away, telling them how happy we were. So they docked me for the

half day, oh well!"

The infinite pathos of it all made a deep appeal to the Professor. This refinement of economic torture was the

invention of a woman grown altogether heartless from a warped moral sense, who no doubt thought she did an honor to abstract justice. Seriously he told

himself he would rather be a tender reprobate than such as she, and taking the old fellow to the outside desk had him indorse the check, quietly slipped

him the twelve dollars, took the paper and, folding it, put it in his pocket. He was in a deep meditation on just what was moral responsibility when his

attention was attracted by Mr. Annan, who had finished shaving the last check.

"What was the matter with old Kunkle?"

"He was in a hurry."

"I will take the check."

"No, thank you, I am not short of funds,"—he would shield the woman—"How is my balance?"

"Not overdrawn I am sure, I shall have a statement for you in a moment," giving orders for the same. In handing it out,

the cashier said:

"By the way, you shall have that gang of beggars bothering you to handle all their paper to save our commission. "

"You charge a commission, I notice."

"Have to, none of them has an account."

"I see, but still you get all their money in the end."

The Professor failed in his effort to shield the reputation of the lady treasurer of the Academy; he might just as well

have given the paper to Mr. Annan, for Kunkle was not slow to tell all whom he met the details of his trouble. Indignation was quite general, finding

vent in load expostulations wherever two or three were gathered together in the village. At the evening mail the matter was discussed and the

treasurer roundly condemned in presence of the Academy driver, who it was well known would report to the authorities. Harry's generosity was on all

lips, his name pronounced with a faith and hope that were inspiriting. Peter Burkett was bold enough to bring the subject up to him personally:

"It's a shame, a darned shame," he avowed, "to do anything like that. I believe in justice and right dealings, but

that's carrying things too far."

"It's a matter of discipline I suppose," excusingly.

"Discipline eh! not on your life, it ain't. It's to show the men they got them under their thumbs. Mr. Kunkle is one of

their oldest and most conscientious employees. I wouldn't blame him if he loafed every time their backs is turned. Twelve dollars a month ain't no

living wage anyhow, and if they only pay that much they only ought to get its equivalent."

"You are a close reader of the Chronicle, I see." "You bet you, and I know where them ideas is coming from."

"How do we stand financially, the Dramatic Society, I mean?" willing to change the topic.

"I got everything 'bout square, been waiting to make a statement, nothing diddin' just now, so we can tote up."

Seating him at the desk at the back of thy store, Peter placed a file of papers before him, then took the book decorated with the picture of the fat butcher from a

drawer, saying:

"Here's your list of expenses and here's your receipts; you just follow the book and I'll call off these and we'll see

how they tally."

Peter's bookkeeping was a lesson in business accuracy; not an item marked in the book but there was an acknowledgement

of payment to correspond. Boxes of tacks for the mounting of scenery, papers of pins for the young ladies of the chorus, an horarium of Uncle Bennett's

and the artists' time, Tom Greavy's bill for the footlights, everything in minutest detail was there. The Professor was in admiration at the exactitude

of the grocer, who, when the list was completed, said,

"One item not accounted for."

"What's that?"

"That New Yorker's bill for the main curtain." "That's paid; have we a balance?"

"Plenty, and we can give you the price of that curtain."

"I'll tell you, Mr. Burket, I am not in the show business for profit. If we have something over and above our

expenses, let us use it for the amusement of the people. Suppose we hold a dance."

"We can give a dance and still pay for that curtain," persisted the grocer. "You must not forget, Professor, the people

of this town are always led to believe they are getting something for nothing, though God knows they don't. They are taught that certain persons are

Providence in the flesh, feeding them as He does the birds of the air. It ain't right. I tell you if we are going to make them demand a just price for

what they give, we must make them pay for what they get. I been on the ground a long time and I know what's needed."

"I intended the dance be complimentary to the society and its friends," objected the other.

"Go ahead and I'll pay the costs out of the treasury, but you send me that New Yorker's bill and take your money."

This was practical sociology; the Professor was coming down from the clouds of theory through his dealings with Peter

Burket and his fellow citizens. These had never heard of Stuart Mill, and Henry George was to them nothing more than a name, yet they were all honor

men in the university of life. Not a muck-raking magazine was on sale in the village, and Dr. Forman was the only one of the assembly who ever mentioned

Standard Oil.

On leaving the store he repeated the dictum of the grocer: "If you are going to make them demand a just price for what

they give, you must make them pay for what they get." Verily he was being instructed by the schoolmasters of the 'hedgerow, the Philosopher of the study

was learning from the Pragmatist of the counter. He was met on the street by Sam Topper, the father of the little miss who sang a solo in the operetta.

Sam was one of the more respected workmen in and around Emmitsburg; he had a large family, was quiet and of a certain social superiority arising from

the fact that his wage was above the normal prevailing in the village. The two were on terms of respectful friendship and Harry was surprised to meet

Topper in his best clothes. Inquiry developed that the latter had been dismissed from his position at the College.

"May I ask what the trouble was?"

"There were several; first, of course, a charge of drinking; then of supplying newspapers to the boys."

"Especially the Chronicle?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you deny it?"

"You are not allowed to deny anything; then I was charged with carrying notes to girls in town since the play."

"Was there any basis for that?"

"Why, some of the cubs brought me letters, most of of them addressed to my own daughter; they didn't know she was

mine, and I stuck them all in the fire."

"What was your work out there?"

"I had charge of the gymnasium and furnaces; between times I did their wheelwright work, that's my trade; my salary was

fifteen dollars a month," with a shade of boasting.

"Munificent!" exclaimed Harry; then, "Mr. Topper, don't want for anything while I am here, and don't return to work for

those people without consulting me."

The story he had just heard mingled with the saying of the grocer in his mind as he pursued his way to the office, a

plan of campaign outlining itself. He must get right down to brass tacks; action more than academic discussion was needed here. The Barons were not

malicious, he told himself, they were the heirs of hidebound tradition. A hundred years before, in another and entirely different economic order, their

regime had been instituted, passing on from year to year without regard for changes in the outer world. Idyllic happiness was considered the result of

continuance of custom; no one was responsible individually, therefore the collective evil.

Before entering the editorial room he hesitated, for he had not met the editor since the return from Washington and he

was young enough to feel shame for his weakness. Without formalities Starling said:

"You have a check in your pocket I shall cash."

"What for why, as the natives put it?"

"We may need it later in our business; we shall run it as a pictorial supplement."

"Festina lame, which again being interpreted means: Hold your horses. We are being flooded with material for the best

kind of copy, but shall not begin the battle just yet. Pardon the mixing of metaphors, it comes from stress of feeling."

"More besides the Kunkle affair?"

"Plenty, " and he rehearsed the matter of Topper's dismissal, softening his denunciation of the authorities in harmony

with his thoughts as to their responsibility. No such refinements of conscience vexed the editor, who asked:

"What are you going to do in case they send for Sam?"

"How near maturity are your plans for the shirt factory?"

"Most of the stock is subscribed for and Seabold is at work on the incorporation."

"It's a go, then?"

"Certainly, we have purchased Bennett's old shop with the lot on which it stands."

"Do you wish me to get in on the work?"

"I don't know, I was anxious at first, but when I realize that you have no permanent interests here, that you'll be

leaving as soon as your health is restored, I hesitate about asking you."

"Don't worry about my interests," hastily and not able to keep down the rising color; "put me down for ten shares of

stock. Does that give me a say in the management?"

"Yes, I shall read you the articles of incorporation."

You might just as well read the 'Code of Hammurabi' in the original hieroglyphs. May I nominate the engineer of the new

concern?"

"If you have a candidate."

"I have, and a text for this week's article! Now we are going to make people demand a just price for what they give we

must make them pay for what they get.'"

During the next hour the scratch of pens, varied occasionally by questions on spelling or punctuation, was all that

broke the silence of the room. The editor was writing a full report of his interview with the postal officials, the assistant developing his text. He

was tempted to openly animadvert on the Kunkle affair, but satisfied himself with a reference to the custom in the mercantile world by which faithful

employees are given each year two weeks' vacation with pay. In revising, he scratched a theoretic portion, inserted a story making the point more

tangible, then rang for the "Devil" and sent out his copy. Lighting his cob pipe, he mused while Starling continued to write and correct. When he, too,

had lighted his pipe, he said:

A penny for your thoughts."

"Do you believe Miss Tyson's voice is of operatic calibre?" bluntly.

"My sincerest conviction; Higbee and I have both told her so; she should have a try-out before some maestro."

"I suppose she should, but I don't like the life for a young girl."

"What are your objections?"

"I can scarcely formulate them; they are the relics of some provincial prejudice inherited from a long line of

simple-minded ancestors. They maybe ridiculous but all the stronger because inexplicable. You really don't know how unprogressive I am when it comes to

the gentler sex. With all my experience I can never accustom myself to seeing a woman take a drink, and to behold one smoking a cigarette is torture to

me. That is certainly provincial enough, in all conscience, and there is something akin to it in my attitude towards women on the professional stage."

"I rather agree with you on the first counts, but cannot see anything unbecoming with a stage life for a young woman

who is level-headed."

"You are foolish to argue with a prejudice, old man, they are born with us or absorbed with our mother's milk. Remember

I have the call on the appointment of engineer. Draw on me at Annan’s for that stock, and, by the way, he shaves these poor devils' checks; we must put

a stop to that."

"I wonder how much prejudice has to do with Harry's attitude to a stage career for Marion?" Galt questioned his blotter

as the door closed.

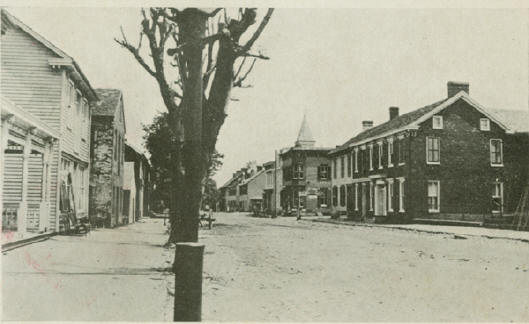

Main Street 1909 - Looking East

It was not an ideal day for walking. The wind blew up and down the street in eddies that gathered dead leaves and dust

and hurled them hither and thither to the melancholy squeaking of antiquated tin signs, which threatened to dislodge themselves at any moment to the

imminent danger of chance passers. The discomfort was increased by the smoke of fires started by foolish householders who thought to keep ahead of

nature in her destroying humor. Beyond the village limits the going was better, the stiff breeze being an inducement to muscular action. The Professor

was taking stock with himself.

Every day seemed to be chaining him more and more to this town, and he did not relish the fact. It was ridiculous to

contemplate Emmitsburg as a field of existence for him, to find himself involved in its problems even to the investment of his money. True, it was no

great amount, but it was a link in the chain, it was helping to make him a man of action, and such he had no desire to become. He was destined to be

un cone-doyen de tout homme qui pence; action was the mere method of passing an enforced holiday.

And Miss Tyson? Here was another disturbing element. In his tower of ivory there was not room for two. Moreover, she

had her own destiny to fill, the world of art was calling to her and he was not to be found an obstacle in her path; rather was it his manifest duty to

help her reach her metier. He was in a glow of physical life and self-renunciation on returning to the Parsonage.

Here the Rector told him Father Flynn had telephoned to have Topper persuaded to ask for his job. Sam was not to know

the President had made the suggestion, lest the College be put in the light of backing down. Harry requested that the matter be left in his hands,

giving assurance the workman would not be the loser. The Rector assented on condition that Sam's family should not suffer.

In the afternoon the following conversation took place over the phone:

"I am sorry, Doctor," said Topper respectfully, "but I have promise of a good job with better pay." "What job?" asked

Father Flynn.

"Engineer at the new factory; it won't start for some months but I am to oversee the setting up of the engine and the

stringing of belts."

"Someone is putting nonsense into your head, Sam; come out and take your position with us."

"I could only stay for the winter anyway, Father; you should get somebody else."

"We cannot get anyone else, as you very well know; you are the only one who understands the boilers, you must not leave

us in the lurch."

"I shall come for the winter, but I can't stay longer."

"Come out then."

"Oh, Father!" hastened Topper, after a nudge from the Professor who stood at his elbow, "I can't work for less than

twenty dollars a month."

"You won't get it."

"Goodbye, Fatherr."

Father Flynn's carriage stood for an hour that night outside Sam Topper's door, a fact remarked and commented upon by

the crowd who came for the evening mail. Within the house the educator argued, the red beard wagging menacingly, but the employee held his ground. Many

insinuations were thrown out about anarchistic loafers who had nothing better to do than sow seeds of discord in the minds of contented people. Sam

acted as though he heard not, doggedly sticking to his demand for increase in wages. Father Flynn finally gave in, extorting a promise that the other

workmen should not know.

Vain precaution, for Sam's audacious demand had first been made over the telephone and Emmitsburg's central had ears

like little pitchers and a tongue which the delft articles do not possess.

Chapter 17

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|