|

The Contralto

Rev. Charles Maloy, C. M.

St. Joseph's Parish, Emmitsburg, Md.

Chapter 17 | Chapter 16 | Chapter 1

Emmitsburg’s social season was full, Scripturally full, good measure, heaped up, pressed down, and running over; a

whirl of life and excitement which made the older inhabitants rub their eyes, and some at times wag their heads and tongues, for the like had not been

in their memory. John Glass ceased to extinguish the street lights at ten, taking it upon himself without seeking the consent of the burgess to allow

them to burn out. Dr. Brawner began to deny that he ever had nightmares, while Whitmore was ever more and more ready to attack Bennett in

religious matters.

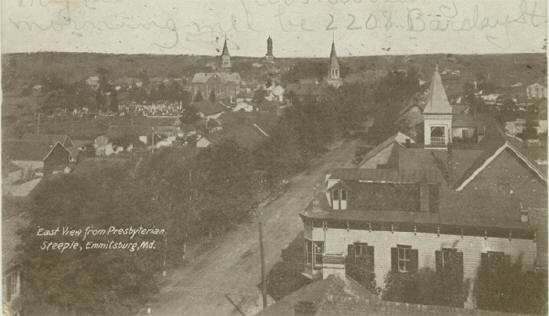

West Main Street taken from Presbyterian Church Steeple ~ 1900

The Professor was the head and front in every movement, the power to induce the cooperation of others being one of his

chief assets. His progress was halted at times by the habits of introspection which his book years had generated, by thoughts and longings for

retirement, and by the question of what personal development there was in it all. He answered himself with the assurance that it was but a temporary

phase of existence, that at the end of the school year with his health restored, master of his vicious thirst, he would return to his own world ready

for real work.

The wife of the musician responded wholeheartedly to the request that she conduct the first dance given to the Dramatic

Society and its friends. It was a revelation, for despite her lack of robust health, the good lady gave the function a Metropolitan air which won the

applause of most who participated. There was no attempt at lavishness, all went off with a simplicity that was charming in the extreme. Mrs. Forman,

Mrs. Seabold, and several other matrons lent assistance, while Mrs. Hopp encouraged with her sometimes caustic comment. The Holy Terror had practically

adopted the Professor, looking with the pride of a mother on all he undertook, even inveigling the Rector into active participation.

Invitations were sent to everyone in the neighbor-hood and lest any be overlooked announcement appeared twice in the

Chronicle, bidding all welcome. For two weeks female hearts were a-flutter with the absorbing question of dress, the mail order establishments of

Chicago did a markedly increased business, while the local dressmaker ran her shop late into the night. The womanly ability to make a beautiful

appearance on a small outlay was a not unnoticed lesson for the economist.

It was a glorious assemblage which gathered in the hall long before eight o'clock. The young ladies were not in

expensive costumes, judged by city standards, but they had the complexions, the ruddy cheeks, the fire in the eye, that no modiste can produce.

Enthusiasm, joy, native pride were unsurpassably in that bevy of girls, while the men, proud in their daughters and sweethearts, had no room for

personal criticism. And how they danced! Programmes, daintily executed by the Chronicle force, were filled before the orchestra under Halm had struck up

the overture.

The old people came too, most of them, to partake of the joyance of the young. They did not dance but sat on benches

along the walls, keeping time to the music with heads and feet, and making comments on the dancers who glided by. Uncle Bennett remained near the door,

for abstinence from tobacco for long was possible to him during only one waking period: when he was in church. Mrs. Hopp dodged hither and thither in

the crowd, assuring everyone her old bones were limbering up under the excitement. Syl Stoner's wife, the mother of ten, wished to help with the supper,

but the Rector would have her take a turn on the floor, so she and bashful Syl danced every set on the card. There were no involuntary "wall-flowers"

for it was moonlight and young farmers for miles around were in town for the occasion.

The Rector and Harry were viewing the scene, both faces alight with reflected pleasure. The latter remarked it was the

first time in years in which he did not feel lonely in a crowd. Vinny, dressed in a simple costume which brought out strikingly her languor, while

emphasizing her surpressed enjoyment, came to them:

"Isn't it just inspiring? and to think we have been dead so long."

"It required the voice of the prophet to waken the bones to life," declared the Rector, nodding towards the Professor.

"Of course, he is the redeemer of Emmitsburg."

"It's a false accusation," said Harry with a laugh; "it's unjust to steal the halo from Mrs. Halm's head and fasten it

on mine. I could never get up a dance, for I cannot do the the first step in a waltz; Terpsichore was on a vacation when I made my debut."

"Don't you dance?" looking at her programme in disappointment.

"Not a step; I never saw anything attractive in it until this evening."

"Oh! someone will be disappointed;" in an undertone as the Rector moved away, "what are you going to do all night?"

"Isn't there something called sitting out?"

"Yes, I always sit out some, as dancing continuously tires me."

"I beg the next sit out, s'il vows plait?"

Behind plants in a corner they watched the passing couples, the Professor speculating on the underlying philosophy of

the scene before him: why people paid to have their dancing done for them by professionals w hen there was so much pleasure to be gotten out o f it by

doing it one's self. The world was growing old, the taedium vitae was marked in the most advanced stages of civilization; when it was young and strong

everyone danced, as everyone, even kings and queens, took part in plays. He was lost for some minutes in these mazes before realizing his duty towards

the girl beside him. On doing so he apologized, and Vinny asked:

"What are you going to advise Marion?" "In what particular?"

"About her voice."

"Really, I don't know; what is your opinion?" hoping to obtain enlightenment, for his duty in the matter was by no

means clear to his mind.

"It will be a grand career for her if she have the vocal qualifications. She has the balance, I am sure. It will be the

proper sphere for the expansion of her soul. She has an infinity of passion under her calm exterior which must find expression in some manner."

He turned in admiration at the insight manifested by this delicate girl, and again unmindful of his part, he speculated

on the advance made by our schools in the development of women. Here was not one of the ideal hausfrau painted by Schopenhauer. It was necessary for the

girl to address him again directly, before he answered her with:

"I see nothing to prevent her; her mother does not object?"

"She is waiting for you, though she doesn't like the idea of the separation involved. I have argued she can travel with

Marion."

"Then there is nothing for me to do but tell her to begin preparations, though it seems rather strange that my

assenting should in any way influence her."

"You are obtuse in some things, Professor, even more so than Emmitsburg," declared Vinny, with a drooping of the

eyelids expressive of a skepticism which was not lost on him.

Endeavoring without success to influence Jimmy Carrigan to lead a partner on to the floor, he was accosted by Marion,

who assured him she was free to sit out without consulting her card. He felt the longing for a cigarette, so requested her to accompany him for a stroll

on the street. Getting her wrap, they walked out in the brisk moonlit air, he lighting his cigarette and inhaling several puffs, knocking the ash off

with the tip of his little finger before speaking:

"My advice to you is to have your voice tried," he said abruptly.

"Rather a hasty conclusion for you, isn't it?" she asked quietly.

"More of a bowing to popular clamor than the result of individual reasoning," with a short laugh. "And I have heard

someone very emphatically denounce the Vox populi, vox Dei principle."

"That was probably when, under the spell of a protracted spasm of personal virtue, he was inducedto sneer at the vapid

vaporings of the herd; he experiences such at times and through its influence sets himself up as a prophet in Israel only to discover later that he is a

Jonah."

"Or a Hamlet whose native resolution is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought," added the girl. It was not a long

walk which led to the end of the paved portion of Emmitsburg; they reached it while he was trying to settle with himself how far he should urge the

taking up of the stage career. Looking at her lightly shod feet he turned back, still debating. The girl laid her hand on his arm, asking:

"Does the matter of my taking up a stage life affect you in any way?"

"Yes," he replied, slowly, electrified by her touch, "I think it does, though just how would be difficult to explain. I

feel an irrational—at least I presume it is irrational—dislike towards it. But I must not allow myself to be guided by sentiment. You have the voice,

the temperament, the tout ensemble for the profession and you are above all level-headed enough to weigh popular applause. It seems to me you will find

in such a life the fullness of your being."

"And that at the sacrifice of all that makes the life of woman worthy."

"Not necessarily," he argued, "there is no antinomy in the case," falling into philosophic phraseology unconsciously;

"I know of one opera singer who is the mother of eight children."

"And brings them up in boarding schools, higher-toned orphan asylums. I am not for

a life; I crave excitement, it is true, but not external I want fullness of being, not the empty vaporings of sapheads

and society dolls. I would rather many Tom Greavy and breed a race of prize fighters than fritter my life away trying to get a message across the

footlights to people dying of ennui."

The girl's voice, though pitched in a confidential tone, was none the less intense as she enunciated these ideas which

seemed an echo of the latest sociological novel. Their appeal was direct and strong to her companion, causing him to inhale a volume of smoke which

produced a fit of coughing. They were in front of the hall, in the door of which stood Bennett, and from which floated the strains of music. Both looked

at each in the moonlight; he tossed away his cigarette end and they prepared to mount the stairs. After passing the old man, who smiled knowingly, the

Professor asked:

"Has Tom proposed?"

"Not yet."

A crowd of dancers was waiting to claim Marion, as she entered the hall, who gazed one to another when they saw her

companion. She was whisked away on the arm of a young and graceful farmer, while Harry and Greavy watched in admiration; the former internally bewailing

his luck which had prevented him from learning to dance. The plumber was speaking:

"Miss Tyson's a brick, Professor; with her for a partner I could take down all the prizes for dancing in the city."

"She is a charming young lady in every respect, Tom."

"I wish she wasn't so well-fixed and educated," ruefully.

"Faint heart never won fair lady."

"But there's such a thing as class; I don't believe in going outside your weight, especially when you're up against a

man more clever than yourself."

"There's another on the mat, then?"

"I guess there's a dozen amateurs, but I don't think Miss Tyson will hold any prelims, she'll call for the main bout

when she's ready."

"Who, in your opinion is the attraction for the windup?"

"Couldn't you give a guess?" winking and edging away.

The open insinuation of the plumber, coupled with Vinny's remark, produced a smile on Harry's face as he thought that

Emmitsburg had him already yoked with Marion. Naturally he meditated in terms of the ring as Tom had started him on that line. He admitted to himself he

was the most clever man in the contest, that he was possibly slated by the girl herself as the main show, for he was an egoist and knew not the meaning

of modesty. But was he in condition, would his moral stamina stay with him in his endeavor to win? As egoists are wont to do, he rehearsed his affairea

de coeur laughing at the lack of serious mishap in form encounters. Absence had not made his heart grow' fonder, Cupid's wounds were rather healed by

it., A letter in the first weeks of separation, then at' greater intervals, at last a remembrance at birthday and Christmas. Tallyrand's philosophy of,

"None but a woman or a fool," and all was over.

Yet in his count with himself in the crowded assembly, Miss Tyson appeared as a decidedly soul filling subject. Her

every attribute passed in review before his mind eliciting admiration. Physically she was certainly good to possess, mentally, she was a tonic. The

absence of anything like coyness in her actions with him flattered his vanity without repelling. It was not defect in the girl that gave him pause, but

in himself. Intellectual men were notoriously poor judges in selecting life mates, being incapable of preserving a balance between the objects of

physical and mental love. Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, showed themselves true philosophers in not entering the married state. Then the vicious habit

of which he was not sure he had divested himself stood out in all its possible results to his inquisition. No, he concluded, better encourage Marion to

take up the stage and meet one who would be truly worthy of her. He was brought to the present as the music ceased and supper was announced.

The repast was disappointing to certain of the guests. A feed, as they were accustomed to call it, was an event in

their lives, a genuine filling that might be talked of for days to come. Mrs. Halm's ideas were not of Emmitsburg development, her supper was a very

simple one which each was compelled to eat standing. Murmurs were quite audible, though fortunately they did not reach the ears of the hostess. Mrs.

Beck, whom anticipation of a feed had brought to the dance, despite her disapprobation of the Professor's course, was loud in her denunciation.

Addressing Dr. Brawner and Bennett, she said:

"Mighty skimpy supper."

"What did you expect," barked the Doctor, "beefsteak and mushrooms?" for this was a ne plus ultra in a country where

fowl was a normal diet.

"No," sneered Bennett, "sauer kraut and bacon."

"Well, I don't call this a supper; it don't compare with the spread they give us at the Academy at Christmas."

"They owe you that," said Bennett, "and you're getting this for nothing."

"I guess it's our own money that's paying for it," she argued, "they might have spent the money that bought these, on

eatings," holding up a little badge surmounted by a small cameo photograph.

The crowd in the supper room had kept the Professor from entering and within earshot of this passage at arms. Now,

after looking at the bauble in the woman's fingers, he remarked one pinned to the lapel of the physician's coat. Gazing at it intently he saw that the

photograph was of and was in the throes of embarrassed indignation when the editor emerged, wearing another.

"What do you think of it?" asked Galt.

"It's a damned fool trick."

"Why?" soothingly, "just move over here, yes are slightly warm."

"Who the devil did that?" pointing to the badge, "The ladies," imperturbably.

"How did they get that photograph?"

"You may search me; I wouldn't get angry about it though, they meant merely to show their appreciation of your work."

"I am not angry, but it makes me feel like a fool. I have done nothing to deserve it. I always object to such things,

they look too much like self-advertisement."

"Don't hide your light under a bushel; let them carry out their little plans. You represent an idea to their minds, a

sort of declaration of independence against the conditions under which they have heretofore lived. Let them wave their flags, they shall forget you soon

enough."

All returned to the dance wearing the badges, which the patronesses had distributed as favors, many of the young ladies

toying with the ribbon attached, as they passed the Professor. Vinny relieved Halm at the piano and the old fellow danced as nimbly with Marion as the

youngest man present. All traditions were broken, for the lights were not extinguished in the building before one in the morning; the chattering groups

which moved down the street and climbed into buggies so charged the atmosphere with merriment that all who partook were jubilant for a month to come.

The Professor walked home with Marion and was silent for a space, for he suffered a spasm of pique because he noticed no souvenir pinned on her dress.

Despite his protest to the editor, he felt the absence keenly.

"Didn't you get a favor?" he asked at length.

"Yes," touching the badge which hung near her heart.

"The other girls pinned them on their breasts." "So they did, it was quite a tribute."

"In which you took no part."

"I am learning to despise the vox populi, or, to vaunt my knowledge of Latin, the vocem populi."

"Or the object of the vocis populi, perhaps."

"Now you are losing that nice even temper of yours: you are inflicting self-imposed punishment; you are quite vain in

certain moods."

"Do you suppose," he exploded, "that I care a snap of my finger for the applause of these people, for their tributes?

As Galt says, they shall forget me quickly enough. What I want is your approbation, your tribute, your applause, Marion."

"Why is my approbation so important?"

"Oh, I don't know," as once more his head got the better of his heart.

"And do you suppose," she asked quickly, "that I care a snap of my finger what Emmitsburg says about my future, about

my stage career? it's your approbation, your consent."

"Why?" he asked brokenly.

"Oh, I don't know," mimicking his tone.

They were at the door, he put out his hand to touch the bell, drew it back, looked at her; they had been perilously

near to a quarrel, the moon had faded.

Chapter 18

Click here to see more historical photos of Emmitsburg

Have your own memories of Emmitsburg of old?

If so, send them to us at history@emmitsburg.net

|